Over the last few months, I’ve spent a lot of time reading through the rulebooks of various tabletop games and getting to play in some others. I really love reading other game books and seeing how these games work, what they put their focus on, and how they use their mechanics to shape the experiences of their players. It’s fun to just read and imagine what playing them might be like, despite not having enough time in this life to actually play all of them!

However, one thing I’ve found really useful by reading through all of this good, good faming content is the magic of pure, unadulterated theft.

There are so many amazing ideas, mechanics, and concepts in the work of designers all over the world available for relatively easy access online. And I have my grubby greedy game master hands and I am stealing those ideas for my Dungeons & Dragons game thankyouverymuch.

One of the most impactful of these (and one of my favorites) is the wonderful, useful, beautifully designed progress clock.

These clocks appear in a few different game systems, though my initial exposure to them was through John Harper’s masterful game Blades in the Dark, published by One Seven. These progress-tracking clocks can be incredibly useful for Dungeon Masters, and are relatively easy to roll into use in your campaign.

Free Progress Clocks Templates

Just want a simple place to start using progress clocks in your campaign? I created a pack of Progress Clocks templates, print-friendly and ready to go.

Grab these templates and you’ll have what you need to start tracking the action and driving the tension in your campaign using these neat tools.

They include some nice examples of in-progress clocks, as well as three variants of clock length you can adapt to any action or tasks in your campaign.

What are Progress Clocks?

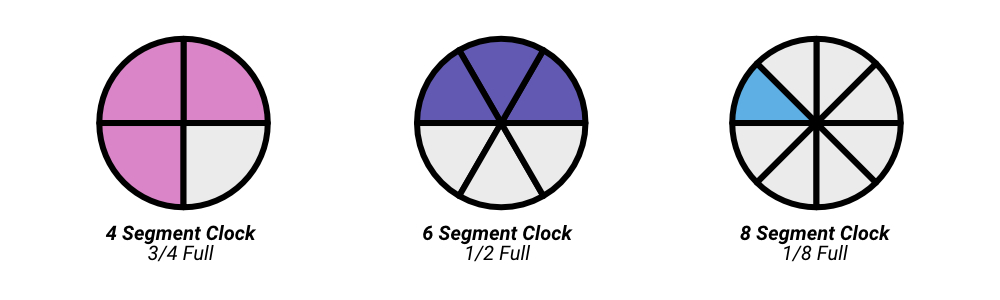

The concept and execution of progress clocks in the context of a tabletop roleplaying game mechanic are both pretty simple at heart: you break something you’d like to track (progress towards an event, how close a group is to being discovered sneaking somewhere, how far along a player is in a crafting task) into a number of segments based on how long or complex it is for that tracked thing to happen. Clocks typically have 4, 6, or 8 segments each, and a single event or task can be tracked using a series of clocks as needed.

Okay, that was more words than I had expected to have to use, but the idea is actually pretty easy once you start seeing what these clocks look like.

The clocks above are pretty typical, with a four-segment clock making less time or work to fill, an eight-segment clock taking more. You might have two eight-segment clocks to track how long until your players are discovered, or three 8-segment clocks.

What is Blades in the Dark?

While this isn’t a post about the game I’m sourcing this idea from, it is worth sharing a little bit about this really awesome game. In Blades in the Dark, your party takes the role of a fledgling criminal organization in a treacherous fantasy city. You plan heists, participate in the power politics of the city, and grow your headquarters, and advance your power and station.

There are a lot of great systems throughout Blades in the Dark, and you’ll find your table playing through some wild situations and telling some very cool stories together.

It’s an overall really great game that feels very different from something like Dungeons & Dragons, and in some really great ways. I can’t recommend it enough!

How can a Progress Clock be used in Dungeons & Dragons or other games?

Consider this situation from any number of Dungeons & Dragons campaigns: your party needs to get to a critical NPC before a group of competitors do or else risking losing access to the information that NPC holds. Without a tracking method, dungeon masters are force to play it by ear and rely on narrative and their own heads to keep things straight. It can be tough to maintain a fair competition between the two groups this way, and keep the (buzzword incoming) verisimilitude intact.

That’s not to say that just keeping things in your head isn’t a perfectly valid way to do this, but bringing in a simply way to keep track can help make it far easier. It also makes what might otherwise be a loose idea of where the party and their competition are into a solidly tracked scene, as well as give your players instant feedback on that progress and drive tension as the clocks fill (if you decide to show them these clocks, more on that later).

Enter the humble progress clock.

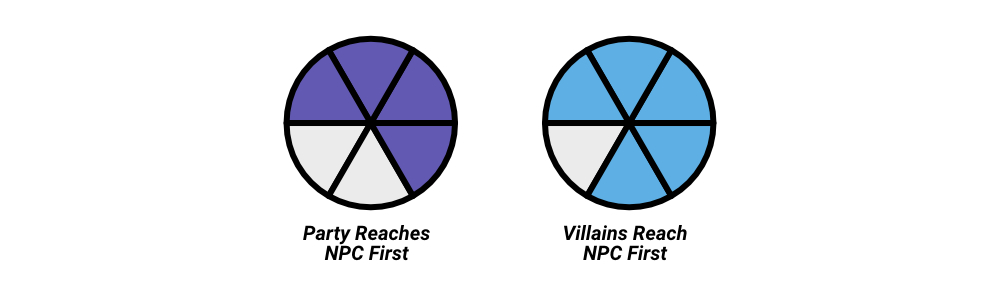

To track this specific narrative, you could whip up two “racing clocks,” a pair of segmented clocks that you track directly against each other and giving each a descriptive name. In this case, “The Party Reaches NPC First” and “The Villains Reach the NPC First” would be pretty descriptive. Then, as the party moves through the action of the scene, you can fill up segments of the clocks to indicate either the party or their competitors making progress towards that NPC.

By filling these clocks as the action in the scene unfolds, you have a hard and fast way to show the impact of that narrative on the game’s outcome. If you show the clocks to the players, they also have instant feedback on the effect their efforts are having on their progress towards their goal and a sense of tension as they see their enemies gaining ground.

The narrative action and the outcomes are still up to the Dungeon Master, of course, but even if one group or the others gets to the NPC first they can use the progress on the opposing clock to help inform what happens next. Say the party fills up their clock and reaches the NPC first, but the villains are only one clock segment behind them. Aside from being a really great tense narrative moment, the dungeon master can really lean into that. Maybe the party secures the NPC initially, but their opponents are so close on their heels that they might have to be dealt with.

Using these clocks to track action and drive that delicious tension in the fiction of your game doesn’t take any control from the hands of the dungeon master and frees their resources up to make the game the best it can be instead of trying to remember where the villains would be or coming up with reasons why they are suddenly in the lead.

What kinds of Progress Clocks are there?

There are actually a few really helpful configurations of progress clocks already that can be really handy to track a pretty broad list of actions in any game, Dungeons & Dragons being no exception. Luckily, they all work pretty similarly and are mostly variations on the same theme, though they remain flexible enough to fit a wide variety of situations.

Danger Clocks

At their heart, many of these clocks will be tracking how close the party is to some kind of danger, whether in the traditional sense or in danger of failing in a goal. Danger Clocks are a pretty straightforward type of clock that gets filled as events progress towards or away from that danger.

If your party is running from some members of the city watch, a danger clock titled “The City Watch Catches Up” could be created to keep an eye on how the party’s actions get them further or closer to those guards. This simple clock is greatfor tracking something that otherwise might feel a bit more amorphous.

Racing Clocks

The example of the players racing against a competitor to get to a goal first is a perfect example of a racing clock. When using a Racing Clock, a set of side-by-side clocks fills up independently depending on the actions that are taken, and the first to win the race to a full clock ‘wins,’ whatever that might mean in the context.

Racing clocks might just be one clock against another single clock, or they might be multiple clocks on either side depending on the complexity of whatever that race to a full clock looks like. They are great at showing progress across competing entities and track that progress in a clear way.

Linked Clocks

Imagine that your party is participating in a bank heist situation where they gain access to the target magical vault. The burglars have only so much time before the guards arrive, and keeping an eye on how close they are to being caught or discovered is critical.

Linked Clocks are set up so that the completion of one clock can ‘unlock’ the next. In this example, by progressing through a clock called “Gain Entrance to the Vault,” a subsequent clock called “The Guards Arrive” would be immediately opened and started.

This style of clock is really just a slight abstraction on a singular Danger Clock, but the serial tracking of events can really apply to a good number of situations in Dungeons & Dragons and other games.

Tug-of-War Clocks

When you’re wanting to track an event with actions that might fill a clock or might empty it, a Tug-of-War Clock is a great tool. Imagine that, in the greater context of your campaign setting, some mystical power is building that will unleash destruction upon the world. If the actions of the players (and other people in the world) helps to prevent that destruction, you can remove segments from a clock that has filled over time and shift them to the opposing clock.

This push and pull of of values between two clocks is an exceptional way to illustrate how the actions of the players are impacting a situation that, without their drive to forestall disaster, would spiral out of control (or, with their failures or betrayals, might not have gotten so bad).

Long-Term Project Clocks

One of my absolute favorite ways to use progress clocks helps me keep track of progress towards longer term projects in Dungeons & Dragons that the rules don’t really handle in a way that satisfies me. Consider a situation where a member of the party is embarking on a large crafting project, one that (per the rules) will take a long time and a lot of rolls over multiple sessions (possibly even months of sessions) to complete.

With a Long-Term Project Clock you could create a series of clocks that represent the number of rolls over time that the player might expect to have to succeed on in order to complete that project. Whenever they sit down to craft, however many successes towards that result will impact the number of segments of clocks that should be filled. Once they’re all filled up, crafting complete!

You can play with long-term project clocks even more by adding interesting mechanics around how failed rolls impact the clocks, as well. I’ve been working with a crafting mechanic that, when the player fails a crafting roll, they actually lose a segment of their current clock. Fail three rolls? Maybe that means they made a mistake and wasted resources, or ruined their tools, and the whole current clock is emptied of progress.

There are lots of great ways these kinds of clocks can be tweaked, making the tracking of longer term projects far more interesting.

Faction Clocks

While the powerful groups and factions of the world are incredibly important in Dungeons & Dragons, the faction affinity systems I’ve seen in play sometimes feel lacking. You do certain things that they may like, or complete jobs for them, and… sometime later… when it just feels right… you get another level of affinity?

Faction Clocks are a way to codify the faction standing of a party in a very clear way, one that allows for a scalable way to manage the affinities of multiple factions and the impact that the party’s behavior and actions has on their regard.

Each faction gets a clock, and segments fill up as the party does things that improve their standing in the eyes of each faction. If they fill up that clock, their affinity with that faction goes up by one, and any events that the change in affinity might trigger, or new benefits being unlocked, can happen then.

And, of course, the reverse is true. By acting against the wishes or goals of a faction, their standing could decrease. This is useful to track, because otherwise it’s hard to know if a group has gone down in overall affinity with a particular group. You can easily track upward momentum, but knowing when that approval is waning can be tough.

This gets even more interesting when tracking factions that are opposed to each other. Impress the local assassin’s guild by taking out a contracted noble? That guild’s faction clock may fill even as that of the city’s ruling organization plummets. This kind of push and pull can help dungeon masters make the interplay between multiple factions and groups far easier to track and have more depth.

Frequently Asked Questions about Progress Clocks

Should I show my players a clock I’m tracking the action on?

This question comes up a lot when people (myself included) start using progress clocks in their games. Knowing when it’s a good idea to share this information with players, possibly to drive narrative tension, or better to let it be a surprise can feel perplexing.

I pinged the amazing folks at the RPG Talk Discord (seriously, if you like tabletop roleplaying games, get thee to this Discord server, the people there are the best) to get their collective thoughts on the matter, and the answer was universally one of “yes, absolutely, show them to your players almost always.”

This makes sense, in retrospect. In almost all cases, certainly in the examples of clocks above. Showing these clocks to a player does nothing to change the narrative in the game. The information that informs their progress on a clock would be generally available to them in some form or another, and seeing a clock just helps make it more clear.

Plus, in many instances, seeing how the clocks are indicating the proximity to failure or success, danger or safety, can really ratchet up the tension in a totally new way.

That said, if there are times you have a clock you want to hide from your players, it can certainly work just as well as a private tracking tool.

If you’re feeling like a particularly crafty dungeon master today, you also have the option of showing the players a clock and not giving it a name, which I guarantee will put them on their toes. Always fun to pop a blank progress clock that fills as the players take all night to decide on a course of action, then watch as they start to panic.

How do I decide how many clocks to use and how many segments each should have?

This one is really more of a gut check, unless you’re doing something like using a clock to track something with a set number of successes required. In most cases it’s a matter of considering how much time a task requires or complexity it has and trying to match that to how many clocks and segments you’ll need to accurately reflect that tracked thing happening.

It does get a bit easier over time as you use clocks more, as you’ll start finding patterns in how your clocks match your players’ behavior and can fine tune them a bit better.

Make clocks with your heart!

I use a virtual tabletop, how can I use Progress Clocks in my game?

There are actually some cool ways to use these in VTTs, though the only one I have direct experience with is for the Foundry Virtual Tabletop.

Foundry has a module available called Clocks 🕑 Progress Clocks, which can be installed to allow the use and display of progress clocks for the dungeon master and players. It can be a little clunky, but it can work well in a pinch.

Roll20 users can use the add-on Progress Clocks, presumedly, to add clocks functionality to your games.

Depending on your virtual tabletop of choice, there may be other options for adding clocks, so take a tour through wherever fine add-on modules are sold.

Gotta Hand it to Clocks

Hah! Hand it to… see what I…

That’s okay, puns aren’t for everyone. Progress clocks, however, can easily be added to any Dungeons & Dragons campaign. Tracking progress towards outcomes, danger, or exciting developments can make a Dungeon Master’s life a little easier and free them up to drive exciting narrative, as well as make the action feel even more real to the players and adding an infusion of tension to the fiction.

One thought on “Using Blades in the Dark Style Progress Clocks in D&D to Drive Tension and Improve DM Tracking”

Comments are closed.